As world leaders are meeting at the UN General Assembly to discuss “urgent action on biodiversity” on 30 September 2020, a new study shows how the Great Auk -a common sea-bird – went extinct without anyone lifting a finger in the 19th century.

For a long time, the Great Auk has been a symbol of extinction, along with the Dodo. Now, in the time of mass extinction, its saga deserves deeper exploration than ever before.

For a long time, the Great Auk has been a symbol of extinction, along with the Dodo. Now, in the time of mass extinction, its saga deserves deeper exploration than ever before.

The Great Auk was a relatively frequent sight on the shores of the North Atlantic until the 19th century. DNA research has recently established that a stuffed bird in the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels is in all likelihood the world´s last living Great Auk, caught in Iceland in 1844.

The stuffed bird can be found in the Royal Belgian Scientific Museum a stones-throw from the European institutions in Brussels. But even if the stuffed bird in Brussels would all of a sudden come alive it could not fly away and join the pigeons and crows loitering around the adjacent European Parliament. The Great Auk was a great swimmer but it could not fly. It even walked awkwardly and as a matter of fact, that very same word may be a derivation of its name.

When three Icelanders, Jón Brandsson, Ketill Ketilsson and Sigurður Ísleifsson, climbed the island-rock Eldey, off the south-western coast of Iceland, in the summer of 1844 two Great Auks that they had spotted were easy prey.

“It was incredible, they were just sitting there looking quite dignified,” Ketill Ketilsson one of the hunters later told British researchers John Wolley and Alfred Newton. The scientists visited Iceland in 1858 to look for Great Auks since it was clear by this time that few of them remained on the island, its last refuge in the world.

After interviewing local farmers and fishermen it emerged that their efforts were in vain. The Icelander told them about the last Great Auks that had been killed fourteen years previously, under growing international pressures for museum specimens. The British scientists´ journals kept in the Cambridge University library tell in detail the story of the killing of the last Great Auk.

Ketilsson told the scientist that when he went after the birds “his head failed him”. If he had some kind of premonition that this was a terrible deed we will never know, but when his colleague Sigurður Ísleifsson strangled the latter of the two birds– it proved to be the world´s last Great Auk.

The Great Auk was extinct.

Don´t blame the killers

Gísli Pálsson, professor of anthropology at the University of Iceland and an author of a new book on the Great Auk warns against blaming the killers of the last Auks. While he admits that he was first drawn to the story about the last Auks because of the story told by the British scientists, he says one must see extinction as a process.

“It is dramatic stuff and it is partly that which drove my interest in the Great Auk. However, to blame the last killers and focus on that is simplistic. In the case of the Great Auk, the mass extinction occurred in Newfoundland in the 18th century. What happened in Iceland in the 1840s is trivia,” Professor Pálsson told the UNRIC website.

Pálsson became interested in the Great Auk when he heard of the existence of the manuscript in Cambridge with the description of the killing of the last Great Auks.

The resulting book “The original penguin and its awkward extinction” has just been published in Icelandic and hopefully, an English language version will follow suit. The Great Auk was the original penguin, lending its name to another species encountered by Europeans in the New World during the age of discovery.

The resulting book “The original penguin and its awkward extinction” has just been published in Icelandic and hopefully, an English language version will follow suit. The Great Auk was the original penguin, lending its name to another species encountered by Europeans in the New World during the age of discovery.

“I have been interested in environmental issues for many years. Recently, my attention has been drawn to the impact of global warming and its devastating effects on life on the planet, notably birds,” Professor Pálsson says. “For me, the case of the Great Auk offered an exciting window into the current disappearance of species.”

“When I was about halfway through the Cambridge manuscript, I realized that this was part of a much bigger drama,” Gísli Pálsson adds. “In it, Newton is putting extinction on the agenda.”

Incidentally, the Great Auk mission to Iceland occurred in 1858, when Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace were about to present their theories of evolution. John Wolley died soon after the Iceland mission but Newton became obsessed with the Great Auk and the extinction of species.

“Newton met Darwin frequently at this time and they have surely discussed this. Newton is experiencing extinction here and now – people are witnessing it “live” in the mid-nineteenth century. Newton draws the conclusion that one can try to prevent it and he later becomes one of the pioneers of nature and bird conservation in the UK.”

Reconstructing or avoiding further extinction?

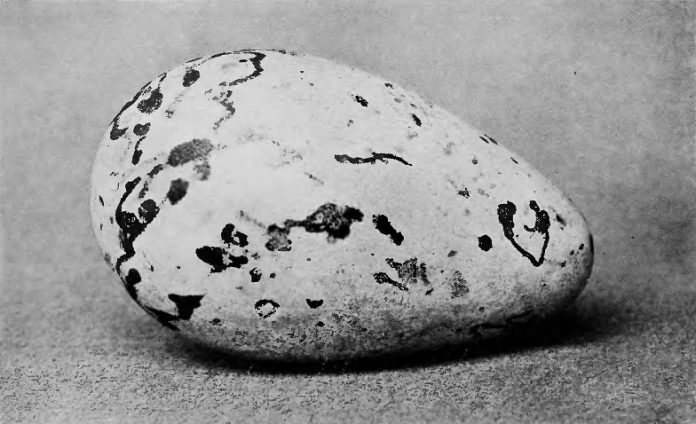

Since everything from eggs to feathers and skin to intestines of Great Auks have been preserved in museums, a lot of DNA exists. This has prompted still on-going discussions among scientists on the feasibility of the reconstruction of the Great Auk.

However, it has been argued that it would be wiser to learn from its fate rather than spending money and energy on such an effort.

“Many species like birds are increasingly and seriously endangered,” says Pálsson. “People talk about the 6th mass extinction and this could be the final one in the history of life on this planet, and it is a human construction in the age of Anthropocene. In the presence of this threat nowadays we need to tend to different species and to ask ourselves what is extinction, what is actually happening and how can we avoid it.”

Pálsson himself is from the Westmanna Islands, in the same region as the Eldey rock where the last Great Auks met their fate. The emblem of his home town is the puffin, which now is considered in danger of extinction in most of Europe.

Pálsson himself is from the Westmanna Islands, in the same region as the Eldey rock where the last Great Auks met their fate. The emblem of his home town is the puffin, which now is considered in danger of extinction in most of Europe.

“I think it is very likely that quite many species will disappear in the next few decades, including the puffin.”

In Iceland, another bird that may disappear locally according to authorities is the raven. Hopefully, the raven, the ancient Nordic bird of wisdom, will inspire world leaders to take action to conserve biological diversity and fight extinctions of species – before it is too late.